Monday, March 26, 2007

productivity gains to Indian economy, thanks to Sri Lanka!

Thursday, March 22, 2007

How others observe

Friday, November 17, 2006

grandfather of free-market theory, Milton Friedman left at 94

Saturday, September 02, 2006

gains and losses from gloabalisation

Monday, August 14, 2006

an awakening in Bihar

Friday, August 11, 2006

economist focus on India's shining prospects

….at the detail, however, …despair at the depth and complexity of the problems India faces. For all its achievements, poverty remains entrenched. Some 260m people survive on less than one dollar a day. Nearly half of the country's children below the age of six are undernourished. More than half of its women are illiterate. Half its homes have no electricity, and in one state, Chhattisgarh, 82% are not even connected by road. Nor is there a huge pot of money to throw at these shortages. The government's average budget deficit, from 2000 to 2004, was exceeded only by that of Turkey. Even when it does spend money, the pipeline between government coffers and the intended beneficiaries is corroded by corruption, and cash seeps out.

…World Bank notes …. this contradiction puzzles fresh observers in three ways. First, they find the rampant economic optimism hard to swallow: it seems to exaggerate changes in the fundamental shape of the Indian economy. Second, even though the economy is booming, the performance of the public sector seems to go from bad to worse. Third, India “is the best of the world, it is the worst of the world—and the gaps are growing.” India's top technology colleges set global standards. Yet “many, if not most, children finish government primary schools incapable of simple arithmetic.”

…. identifies the two most pressing needs for action by India's government: to make the public sector better at delivering basic services; and to sustain growth at high levels and extend its fruits to more people. From this simple but persuasive analysis come the two biggest dangers to India's future. Failure to reform public-sector services will render even high growth and farsighted policy ineffective in ending poverty; and, unless checked, growing inequality between regions, and between town and country, will heighten social tensions.

The shortcomings of the public sector are evident in almost all its functions. India, for example, has a government committed to providing all its people with health care. But there are only five countries in the world where a lower proportion of spending on health comes from the government—just 21% (compared with, for example, 45% in America). So even the poor are paying for private health care. A survey has also found that health care absorbs a bigger share (27%) of low-level “retail” bribery than any other government function. (This may shock some policemen.) Another found that between 1999 and 2003 the percentage of children fully immunised against childhood diseases had fallen from 52% to 45%.

Similarly, in many of India's towns, more than half the children are in private schools. A nationwide survey, based on unannounced visits to government schools, found that less than half the teachers on the payroll were there and teaching. Whereas, in many poor countries, city residents enjoy a 24-hour water supply, in many Indian cities the taps are dry for all but a few hours a day. The rich pay for pumps, bore-wells and storage tanks. The poor queue for hours at standpipes and water lorries.

The public sector tends to be worst at delivering services in India's poorest states. These are, in relative terms, becoming poorer, not because their growth is declining, but because they have failed to match the acceleration achieved since 1991 by India's richer regions and cities. Parts of the country are, in terms of living standards, on a par with Mexico. Parts are as poor as sub-Saharan Africa.

The gaps are showing

Although India has, compared with other countries, a relatively equal distribution of income, it is a deeply unequal society, partly because of its legacy of social stratification and exclusion. The caste system is proving resilient, and there is evidence that, in some respects, the prejudice against girl children is worsening. In rich areas, sex-selective abortion is leading to highly skewed sex ratios at birth. Nor is the bias any less among the poor. A girl born in the early 1990s was 40% more likely than a boy to die between her first and fifth birthdays.

… The beauty of reducing the country's myriad problems to two big, related, ones, is that of all simplification: it makes the solutions seem simpler, too, even if this economic diagnosis of India's ills suggests cures that are mainly political.

… It is not the policies that are failing so much as the machinery for implementing them. In electoral politics, good policy is often forgotten for vote-grabbing promises of jobs, contracts and subsidies. …India is big enough to have plenty of stories of successful reform that can be imitated: most involve making providers of taxpayer-financed services more accountable for their delivery. Spreading those lessons should not be beyond the world's biggest democracy.

Friday, August 04, 2006

economists' (valuable) time in blogging???

…there is here a problem of the division of knowledge, which is quite analogous to, and at least as important as, the problem of the division of labour,� Friedrich Hayek told the London Economic Club in 1936. What Mr Hayek could not have known about knowledge was that 70 years later weblogs, or blogs, would be pooling it into a vast, virtual conversation. That economists are typing as prolifically as anyone speaks both to the value of the medium and to the worth they put on their time.

…economists from circles of academia and public policy spend hours each day writing for nothing. The concept seems at odds with the notion of economists as intellectual instruments trained in the maximisation of utility or profit. Yet the demand is there: some of their blogs get thousands of visitors daily, often from people at influential institutions like the IMF and the Federal Reserve…most active “econobloggers� are Brad DeLong, Gregory Mankiw, Gary Becker and Richard Posner, a long list on Mark Thoma’s blog.

Wednesday, August 02, 2006

errors in economics and the aftermath

Sometimes it is the individual committing an economic error who alone bears the cost. An example is the investor who seeks out and follows financial analysts' advice on the purchase and sale of stocks, despite overwhelming statistical evidence demonstrating that, even if such advice were offered without cost, it would generally be valueless or worse. Professional recommendations on stock market purchases and sales have repeatedly been shown to be totally unreliable. Indeed, they must be so because, as the data demonstrate, the behavior of securities prices approximates what statisticians call a "random walk." Random behavior is, by definition, inherently unpredictable even by the best-informed and most intelligent analyst. But stock market analysts' advice is even worse than this for the investor, on two scores. First, it is not costless. The investor is forced to pay for bad information and is thereby put in the position of a bettor in a gambling casino, where the outcomes are not just random but are systematically biased to bring a predictable rake-off to the gambling house. Second, whether or not as a deliberate dereliction of duty, frequent sales and purchases of securities that benefit the stock market analysts' own firms are characteristic of their recommendations. These transactions multiply the investor's total payments to these firms and, incidentally, materially increase the investor's tax bill.

…notable example was the belief that an essential step in extracting an economy from recession or depression is elimination of deficit spending by the government. While there is no longer agreement by economists that expansion of such spending is invariably a sensible step, it is recognized that the simpleminded argument that leads many non-specialists to conclude that such deficit spending threatens to bankrupt the nation is an exercise in the "fallacy of composition." This fallacy is the presumption that a relationship that is valid for each individual must automatically be valid for the entire group of these persons. One elementary example entails voluntary exchange between two informed and rational individuals and the conclusion that such an exchange must offer some benefit to each of them, or at least no loss to either (otherwise, the prospective trade participant who stood to lose from the transaction would simply refuse to trade). The fallacy of composition enters when this insight about trade between individuals is applied to trade between two countries, where it is neither self-evident nor generally true that exchanges must invariably benefit both countries.

Turning to the issue of deficit spending, the standard view stems from the observation that an individual who is in financial difficulty because of persistent spending beyond his means must somehow succeed in curtailing his overspending now and in the future if he is to avoid exacerbation of his financial troubles. The inference from this observation drawn by analogy for a depression-beleaguered government--whose tax revenues have fallen as a consequence of reduced incomes and whose expenditure has been driven upward by rising obligations--was that, just as in the individual case, fiscal retrenchment was essential. Governments in that position characteristically find themselves plagued by rising debt and the evident, if questionable, conclusion was that material retrenchment was urgent and unavoidable if financial catastrophe for the country was to be avoided.

But, one of the central propositions to emerge in the course of the Keynesian revolution was that this prescription for retrenchment was the precise opposite of what such a situation requires. Rather, an effective governmental weapon--indeed, a critical component of the counter-depression policy that Abba Lerner dubbed "functional finance"--is enhancement of deficit spending, entailing rising public debt, with the shortfall to be made up during the other end of the business fluctuation, when inflation replaces unemployment as the primary threat to the economy.

The way in which the fallacy of composition enters the matter is quite straightforward. Increased spending by an individual (without any offsetting rise in earnings) spells financial peril. For the community of individuals, taken as a group, the situation is, at least in the simplest Keynesian view, usually the reverse of this. The more the government increases spending without a corresponding rise in tax revenues, the better off the community will be economically. This act of magic occurs because the very deficit spending must put purchasing power into the hands of the public, which in turn will serve to raise demand for goods and services. And in a depressed economy, anything that serves to offset lagging demand must be helpful, because it will expand sales, elicit enhanced production, and provide additional jobs. So deficit spending by government is a stimulus of economic activity and a source of added income for the society as a whole. This stimulus effect also helps to cut the government's budget shortfall by automatically adding to total tax revenues as private incomes rise, and by cutting needed government expenditures, such as outlays for support of the unemployed. As Keynes himself pointed out, the apt parable is that of the legendary widow's cruse, which kept refilling itself as its contents were extracted. For, if the argument is valid, it indicates that the more the government overspends, the more net income it can hope to have available in the near future.

This argument, though not universally accepted by economists today, was certainly rejected by many, including President Franklin D. Roosevelt, in the 1930s. It is at least arguable that the resulting efforts to curb government overspending protracted the Great Depression, creating a second economic decline toward the end of the decade, with termination of the Depression left to the onset of the Second World War, which once again imposed substantial deficit spending on the government. If it is true that insufficient government spending exacerbated the effects of the Depression, then it is surely difficult to dispute the conclusion that here was an economic error that caused great and widespread harm, increasing unemployment, reducing incomes, and keeping output and accumulated wealth of the society down well below what it might otherwise have been.

There is an associated popular misunderstanding, which strengthened the determination of the opponents of deficit spending. This is the conclusion that government deficit must constitute a "burden upon our grandchildren." There are, it must be admitted, circumstances in which this could be true, and one must not go so far as to deny the possibility of any detrimental consequences of government debt for future members of the community. But the common and assuredly naive variant of the idea is yet another example of the fallacy of composition. That assets lost by injudicious expenditure during an individual's lifetime can impoverish her heirs is evident. But for a nation, matters are far different. Thus suppose, for example, that a government greatly increases its current expenditure on military equipment, financing it by borrowing, through the issue and sale of additional government bonds. The labor, steel, power, and other inputs that are used to manufacture the armaments immediately become unavailable for civilian use. This is a burden that fails upon the public at once and need not in any way affect future generations whose supply of factors of production need not thereby be diminished. The labor that today is shifted from production of autos to the manufacture of tanks does not reduce the availability of labor to consumers 20 years hence. Reduced resource availability that results from government deficit spending, then, is primarily a burden upon the current generation, not those of the future.

It is not even true that government debt incurred today need entail a financial problem tomorrow, when the debt is to be repaid. But from what source is the repayment to be made? Suppose, for concreteness, that the government bonds that financed the debt are scheduled for redemption 20 years after the deficit spending occurred, and that at that date the government raises taxes by an amount just sufficient to cover the X-dollar debt. Then that is surely a burden for those who must pay the X dollars in taxes, but it is accompanied by a rise of exactly X dollars in the cash that becomes available to the bondholders. If the bonds are not held by foreigners, what will happen at the date of repayment is that the money that financed the purchases will simply have been transferred from one group of citizens to another. Indeed, even that need not take place to any marked extent. If, for example, the government bonds are held by individuals roughly in accord with their incomes, the wealthier the individual, the greater his holdings, then if the tax is also proportioned to income, the repayment process need not incur any significant transfer of purchasing power. The money will be taken from the wealthy, and promptly returned to the same individuals. In the words of Adam Smith, what will have been entailed is simply a transfer of money from the right pocket of the taxpayer to the left.

In short, viewed in terms of its substance, the burden of government expenditure is a burden upon the present, not upon the future. Yet this was apparently not understood by earlier generations of economists and certainly not by the general public. And the error was not just a matter of academic interest. Rather, by preventing the actions that promised a speedy recovery from recession or depression, it had marked and unfortunate consequences for the general welfare.

… to the key misunderstanding, in terms of policy, engendered by the failure to understand the nature of the cost disease: the idea that the cost disease will force society (or the government that provides the finances) to retrench and eventually cut back on vital health care and education because of the mistaken belief that their rising cost must make them increasingly unaffordable to society. This belief, it turns out surprisingly, is virtually the reverse of the truth.

In actuality, the very forces that create the cost disease make these services ever more affordable to society. This is so because the source of the problem is that, although productivity is growing in almost every industry, in some industries (particularly personal services) it is growing more slowly than in others. But if output per worker and output per work hour are rising in virtually all industries, then a given quantity of any bundle of outputs requires an ever smaller share of the labor force for its production. What society must do is use part of the cost savings from the industries (like manufacturing or telecommunications) in which productivity is growing at a rapid rate to pay for the personal services (like health care and education) in which productivity is growing at a relatively slower rate. It is simply not true that society cannot afford those costs. On the contrary, rising productivity means that society can afford to consume more of each and every product. It is this observation that led the late Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan to describe the cost disease analysis as a profoundly optimistic diagnosis.

The danger is that governments, the primary source of financing of these services in most countries, will decide that the cost burden is beyond their capacity to finance, and will decide that cutbacks are their only option. This is already happening in many of the industrialized countries, where an increasing set of medical procedures are denied to patients and cutbacks in financing of universities and their teaching and research activities are all too common. This is unfortunate because, as is shown by the cost disease analysis, their unaffordability is a fiscal illusion, and retrenchment of these arguably vital activities is an unnecessary if understandable response to this illusion. Here, surely, is a case in which misunderstanding can result in totally avoidable damage to the social interest.

The possibility that, in a wide variety of circumstances, a rise in price may be a substantial benefit to the public is something that people untrained in economics always find extremely difficult to accept. ..If a price, such as the price of crossing a crowded bridge or the price of environmentally damaging gasoline, is set very low, then consumers will be provided an incentive to exacerbate the problems. These market signals will induce them to add to the crowding or to the environmental damage even further….. One telling illustration is the way that landing privileges at crowded airports are often priced. Airports become particularly congested at peak hours, just before 9 a.m. and just after 5 p.m. This is when passengers most often suffer long delays. But many airports continue to charge bargain landing fees throughout the day, even at those crowded hours. That makes it attractive for small corporate jets or other planes carrying only a few passengers to arrive and take off at those hours, worsening the delays. Higher fees for peak-hour landings can discourage such overuse, but they are politically unpopular, and many airports are run by local governments. So we continue to experience late arrivals as a normal feature of air travel.

We know that inappropriately low prices caused nationwide chaos in gasoline distribution after the sudden drop in Iranian oil exports in 1979. In times of war, constraints on prices have even contributed to the surrender of cities under military siege, deterring those who would otherwise have risked smuggling food supplies through enemy lines. Low prices have also discouraged housing construction in cities where rent controls made building a losing proposition. Of course, in some cases it is appropriate to resist price increases--as when unrestrained monopoly would otherwise succeed in gouging the public, and when rising prices fall so heavily on poor people that rationing becomes the more acceptable option. But before tampering with the market mechanism, we must carefully evaluate the potentially serious and even tragic consequences that artificial restrictions on prices can produce, particularly when scarcity threatens or is already damaging the public welfare.

It is not easy to accept the notion that higher prices can serve the public interest better than lower ones. Politicians who voice this view imperil their jobs. Because advocacy of higher prices courts political disaster, the political system often rejects the market solution that automatically raises prices when resources suddenly become scarce. And that only enhances the shortages.

…. economists are usually strongly predisposed to favor free trade, globalization, and market-driven apportionment of industries among nations. But this orientation has led many of them to conclude that when a portion of an economic activity or even an entire industry moves from a high-wage to a low-wage country as a result of an increase of productivity in the latter, both the gainer and the loser of the industry can be expected to benefit. In particular, while some individuals in the country from which the activity has emigrated will evidently be harmed, on this view the country as a whole will normally benefit from the reduced costs of the products whose production has moved abroad, and benefit sufficiently to compensate for the damages and more.

Those who believe that macroeconomic policy can effectively limit involuntary unemployment have reason to conclude that loss in the total number of jobs is not an inevitable consequence of globalization, though it does undoubtedly threaten the working positions of at least a few directly affected individuals, for whom the consequences must not be taken lightly. But though we may reject the popular view that globalization is a major threat to employment and an instrument of extensive job loss, we cannot deny that there is reason to be concerned with at least the short-term effects on wages in both developing and developed lands. International competition can influence relative input prices and thereby determine whether machinery will be substituted for labor, for example, or whether skilled labor will be substituted for unskilled. There are, also, more direct implications for wages. Surely, the increased use of computer programmers in India can be expected to reduce the demand for such skills in the United States below what it might otherwise have been.

For the developing countries, economic history suggests that an industrial revolution initially tends to depress real wages and real living standards, thus supporting the concerns of those who fear the consequences of globalization for the world's less prosperous nations. Though the British industrial revolution is usually considered to have taken off about 1760, it was probably not until approximately 1840 that wages began to rise. Data on life expectancy and average height also indicate that the spread of innovation was accompanied by worsening of the economic status of wage earners, perhaps in part as a result of the move from the countryside to crowded, unsanitary slums; the evidence indicates that the US labor force underwent a parallel trajectory. One may surmise that part of the explanation was a rise in the power of employers and an inability of the workers, in the absence of labor organizations, to resist.

The opponents of globalization draw attention to a similar phenomenon in twenty-first-century globalization, with multinational employers subjecting their employees to disturbingly low wages and shocking working conditions, particularly on the criteria widely accepted in the affluent economies (though by no means always adhered to even there). Thus, even if globalization is a very promising influence for the more distant future prospects of the developing countries, there is good reason to fear that in the short run the workers in those lands may gain little and may even lose out in the initial stages of globalization.

It can be argued that all this is transitory and that in the long run the lower-income groups in the developing countries will be better off, as has indeed been true in the developed economies. But the process can easily take decades. We cannot just ignore decades of very substandard earnings that amount to preservation of grinding poverty in a developing country or the permanent structural unemployment in a developed economy that can beset older workers whose skills are made redundant by innovation, and for whom the acquisition of new skills is not a practical option. These are hardships that constitute an extremely painful economic pathology for the affected individuals. At the very least, one can argue that those who stand to benefit from the process should be expected to agree to provide systematic and substantial assistance to the victims, presumably through government channels, and supported liberally by the wealthier communities. If that is not acceptable politically, there is surely little that can be said convincingly in support of a contention that the suffering of the victims will be justified by the promised future benefits to their descendants.

If the arguments of this paper are not themselves in error, what I have shown is that the economics profession can, indeed, sometimes show the layperson the error of his or her more common-sense thoughts. But not always. Sometimes the errors and the route toward correction go the other way. This observation is not meant in any way to denigrate the work of my colleagues. After all, it is only through careful analysis that one can discover where it is the specialist who has been wrong and where the often exceedingly fallible common sense of those with no formal training in the field has turned out to be closer to the underlying reality. We have also seen that misunderstanding in the field of economics can have consequences beyond pushing researchers and teachers in misguided directions. Perhaps as much as any discipline, erroneous economic analysis and conclusions can elicit policies severely damaging to the public interest. And, in this, I believe that we economists do have something to answer for. We are all too prone to put more faith in the implications derived from our quite appropriately simplified models, and to draw from those implications policies that really only apply universally in the artificial world of the constructed model…

Tuesday, June 27, 2006

Indian Model

Wednesday, June 21, 2006

rental markets for wives!!!!

Atta Prajapati, a farm worker who lives in Gujarat state, leases out his wife Laxmi to a wealthy landowner for $175 US a month. A farm worker earns a monthly minimum wage of around $22. Laxmi is expected to live with the man, look after him and his house, and have sex with him.

The male-female ratio is becoming increasing skewed across India because many parents abort female fetuses, preferring sons to daughters.

Female children must be married off, and to achieve that a daughter's parents usually have to pay the groom's family a dowry of cash and gifts - often a massive burden on the parents' resources.

Dowries were outlawed in 1961, but the practice is still common and the law ill-enforced.

The nationwide number of girls per 1,000 boys declined from 945 in 1991 to 927 in 2001, according to the 2001 national census.

It is not unusual for wealthy families to hire housekeeping staff in India, but prostitution is illegal.

The lack of marriageable girls ...has also led to booming business for bride brokers, who are paid to find a woman for a man to marry.

Brokers charge a groom's family up to $1,520, and the girl's family will receive around $435...

Perhaps the obligation of expenditure on both sides of the family in marriages are required, thus increasing competition for wives and perhaps raising the value of female offspring

Wednesday, February 08, 2006

IMF's role to rethink!!

This is very interesting situation. Here is the piece by William McQuillen of Bloomberg.

The International Monetary Fund's loss of two of its biggest borrowers last month has left the lender and renewed questions about its role in the global economy. In the past six weeks, Brazil made early repayment of $15.5 billion it owed and Argentina repaid $9.5 billion in debt two years ahead of schedule, closing the accounts of the International Monetary Fund's first- and third-largest borrowers. The enticement to pay the debt -- foreign reserves that have swelled as Latin American economies rebound from recession and investors' appetites for government bonds grow -- is present in other large borrowing nations, including Pakistan, Serbia and Ukraine, which have hinted that they, too, may sever ties to the lender.

"In good times, nobody goes to the IMF," said Liliana Rojas-Suarez, a former International Monetary Fund (IMF) economist who is now at the Center for Global Development in Washington. The result is a loss of interest income that prompted the IMF to lower its earnings forecast by about 40 percent for the fiscal year ending in April. The fund now expects a budget shortfall of more than $116 million this year, emboldening critics who have called on the Washington-based fund to scale back its lending and focus more on dispensing economic guidance.

"This should force the fund to ask what they are doing and what they should be doing," said Allan Meltzer, a professor at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh who led a 2000 U.S. congressional commission that examined the IMF. "If it is just business as usual, the fund will be becoming less relevant." The fund may invest some of its reserves as it looks for ways to make up for the decline in net income, said Thomas Dawson, a spokesman for IMF Managing Director Rodrigo de Rato.

The IMF was founded at the end of World War II to promote global economic stability. The fund typically makes loans to countries on the condition that the borrowers undertake economic policy changes such as adjusting their balance of payments or reducing inflation. With elections nearing, those conditions grew unpopular in Argentina and Brazil, where the public has blamed their countries' economic crises on IMF-mandated changes.

Those countries aren't alone. Pakistan, the IMF's third-largest debtor now that Argentina has walked away, is carrying $1.51 billion in debt and says it is seeking to cut its dependence on the fund; Ukraine, the fourth-largest debtor, said in 2004 it probably would decline any additional assistance; and Serbia, which owes the IMF about $874 million, said last month that it wouldn't borrow any more. A year ago, Russia repaid early its $3.3 billion debt to the IMF after seven years of economic expansion; in 2003, Thailand finished paying off its obligations two years ahead of schedule.

"This plays very well politically in those countries," said Desmond Lachman, who spent 24 years as an IMF economist and is now a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, a Washington think tank. "Prepaying the IMF is declaring independence." Greater liquidity in capital markets has given nations other places to go for loans, while low interest rates have made financial emergencies less likely. There hasn't been a worldwide economic crisis that has required the IMF since the Asian and Latin American turmoil of the late 1990s.

The IMF's projected budget shortfall for fiscal 2006 has increased to $116 million from $26 million as a result of the interest-payment revenue it will lose because of the early debt repayment by Brazil and Argentina. Its total operating budget is $2.3 billion, almost all of which is funded by interest income. The IMF is hardly going broke: The lender can access about $139 billion, mostly through the financial commitments of its member countries, a November financial statement showed. The fund also has stockpiled more than 100 million ounces of gold, which would be worth more than $56 billion at today's market prices. In a cyclical world economy, there will probably be a time when governments again rely on the IMF for loans, Mr. Dawson said. Until then, the IMF is content with less influence, he said.

bloggers for corporates

…. Scandals at Enron and WorldCom destroyed thousands of employees' livelihoods, raised hackles about bosses' pay and cast doubt on the reliability of companies' accounts; labour groups and environmental activists are finding new ways to co-ordinate their attacks on business; and big companies such as McDonald's and Wal-Mart have found themselves the targets of scathing films. But those are just the enemies that companies can see.

….The spread of “social media� across the internet—such as online discussion groups, e-mailing lists and blogs—has brought forth a new breed of brand assassin, who can materialise from nowhere and savage a firm's reputation. Often the assault is warranted; sometimes it is not. But accuracy is not necessarily the issue. One of the main reasons that executives find bloggers so very challenging is because, unlike other “stakeholders�, they rarely belong to well-organised groups. That makes them harder to identify, appease and control.

food for thought?

• Decades of underinvestment in rural areas, which have little political clout

• Wars and political conflict, leading to refugees and instability

• HIV/Aids depriving families of their most productive labour

• Unchecked population growth

Wednesday, December 21, 2005

darwinism: survival of fittest??

….It was Spencer… who invented that poisoned phrase, “survival of the fittest�. ..originally applied it to the winnowing of firms in the harsh winds of high-Victorian capitalism, but when Darwin's masterwork, “On the Origin of Species�, was published, he quickly saw the parallel with natural selection and transferred his bon mot to the process of evolution…. became one of the band of philosophers known as social Darwinists. Capitalists all, they took what they thought were the lessons of Darwin's book and applied them to human society. Their hard-hearted conclusion …. was that people got what they deserved—albeit that the criterion of desert was genetic, rather than moral. The fittest not only survived, but prospered. Moreover, the social Darwinists thought that measures to help the poor were wasted, since such people were obviously unfit and thus doomed to sink.

... For 100 years Darwinism was associated with a particularly harsh and unpleasant view of the world and, worse, one that was clearly not true—at least, not the whole truth. People certainly compete, but they collaborate, too. They also have compassion for the fallen and frequently try to help them, rather than treading on them. For this sort of behaviour, “On the Origin of Species� had no explanation. As a result, Darwinism had to tiptoe round the issue of how human society and behaviour evolved….. the disciples of a second 19th-century creed, Marxism, dominated academic sociology departments with their cuddly collectivist ideas—even if the practical application of those ideas has been even more catastrophic than social Darwinism was.

…the real world …penetrates even the ivory tower. The failure of Marxism has prompted an opening of minds, and Darwinism is back with a vengeance—and a twist. Exactly how humanity became human is still a matter of debate. But there are, at least, some well-formed hypotheses... they rely not on Spencer's idea of individual competition, but on social interaction. That interaction is…sometimes confrontational and occasionally bloody. ..it is frequently collaborative, and even when it is not, it is more often manipulative than violent.

Modern Darwinism's big breakthrough was the identification of the central role of trust in human evolution. People who are related collaborate on the basis of nepotism. It takes outrageous profit or provocation for someone to do down a relative with whom they share a lot of genes. Trust….allows the unrelated to collaborate, by keeping score of who does what when, and punishing cheats.

Very few animals can manage this. .. outside the primates, only vampire bats have been shown to trust non-relatives routinely. (Well-fed bats will give some of the blood they have swallowed to hungry neighbours, but expect the favour to be returned when they are hungry and will deny favours to those who have cheated in the past.) The human mind…seems to have evolved the trick of being able to identify a large number of individuals and to keep score of its relations with them, detecting the dishonest or greedy and taking vengeance, even at some cost to itself. This process may even be…the origin of virtue.

The new social Darwinists (those who see society itself, rather than the savannah or the jungle, as the “natural� environment in which humanity is evolving and to which natural selection responds) have not abandoned Spencer altogether... they have put a new spin on him. The ranking by wealth ….is but one example of a wider tendency for people to try to out-do each other. .. competition, whether athletic, artistic or financial, does seem to be about genetic display. Unfakeable demonstrations of a superiority that has at least some underlying genetic component are almost unfailingly attractive to the opposite sex. Thus both of the things needed to make an economy work, collaboration and competition, seem to have evolved under Charles Darwin's penetrating gaze.

This is ..full of ironies…. One is that its reconciliation of competition and collaboration bears a remarkable similarity to the sort of Hegelian synthesis beloved of Marxists. Perhaps a bigger one… is that the Earth's most capitalist country, America, is the only place in the rich world that contains a significant group of dissenters from any sort of evolutionary explanation of human behaviour at all. …. suggests a constant struggle, not for existence itself, but between selfishness and altruism—a struggle that neither can win. Utopia may be impossible, but Dystopia is unstable, too, as the collapse of Marxism showed. Human nature is not, … red in tooth and claw, and societies built around the idea that it is are doomed to early failure.

Of the three great secular faiths born in the 19th century—Darwinism, Marxism and Freudianism—the second died swiftly and painfully and the third is slipping peacefully away. But Darwinism goes from strength to strength. If its ideas are right, the handful of dust that evolution has shaped into humanity will rarely stray too far off course….

Thursday, December 15, 2005

Wednesday, December 07, 2005

from seattle to hong kong: multi trade negotiations

In a prelude to the rounds of multi trade negotiations under WTO, the Foreign Affairs has come up with a special issue with some of the world's top experts on international trade consider what will be necessary for the Doha Round to succeed — and what might happen if it does not.

Monday, December 05, 2005

remittances: economic lifeline of many developing countries

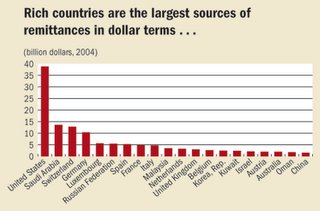

Migrants from developing countries send home part of their earnings in the form of either cash or goods to support their families, which are known as workers' or migrant remittances. The recent years there have been growing trend, and now represent the largest source of foreign income for many developing countries. A senior economist at the World Bank's Development Prospects Group, Dilip Ratha has examined the issue in the recent issue of Finance and Development of IMF publication.

…. Worldwide, officially recorded international migrant remittances are projected to exceed $232 billion in 2005, with $167 billion flowing to developing countries. These flows are recorded in the balance of payments…Unrecorded flows through informal channels are believed to be at least 50 percent larger than recorded flows. …remittances large…they are also more evenly distributed among developing countries than capital flows, including foreign direct investment, most of which goes to a few big emerging markets…. remittances are especially important for low-income countries.

How is the money transferred?

..typical remittance transaction takes place in three steps.

- the migrant sender pays the remittance to the sending agent using cash, check, money order, credit card, debit card, or a debit instruction sent by e-mail, phone, or through the Internet.

- the sending agency instructs its agent in the recipient's country to deliver the remittance.

- the paying agent makes the payment to the beneficiary. For settlement between agents, in most cases, there is no real-time fund transfer; instead, the balance owed by the sending agent to the paying agent is settled periodically according to an agreed schedule, through a commercial bank. Informal remittances are sometimes settled through goods trade.

The costs of a remittance transaction include a fee charged by the sending agent, typically paid by the sender, and a currency-conversion fee for delivery of local currency to the beneficiary in another country. Some smaller money transfer operators (MTOs) require the beneficiary to pay a fee to collect remittances, presumably to account for unexpected exchange-rate movements…. remittance agents (especially banks) may earn an indirect fee in the form of interest (or "float") by investing funds before delivering them to the beneficiary…float can be significant in countries where overnight interest rates are high.

Why are remittances helpful?

Remittances are …transfers from a well-meaning individual or family member to another individual or household….targeted to meet specific needs of the recipients and thus, tend to reduce poverty…..World Bank studies, based on household surveys conducted in the 1990s, suggest that international remittance receipts helped lower poverty (measured by the proportion of the population below the poverty line) by nearly 11 percentage points in Uganda, 6 percentage points in Bangladesh, and 5 percentage points in Ghana.

How are remittances used? In poorer households, they may finance the purchase of basic consumption goods, housing, and children's education and health care. In richer households, they may provide capital for small businesses and entrepreneurial activities. They also help pay for imports and external debt service, and in some countries, banks have been able to raise overseas financing using future remittances as collateral.

Remittance flows tend to be more stable than capital flows, and they also tend to be counter-cyclical—increasing during economic downturns or after a natural disaster in the migrants' home countries, when private capital flows tend to decrease. In countries affected by political conflict, they often provide an economic lifeline to the poor. The World Bank estimates that in Haiti they represented about 17 percent of GDP in 2001, while in some areas of Somalia, they accounted for up to 40 percent of GDP in the late 1990s.

Is there a downside?

…a number of potential costs associated with remittances. Countries receiving migrants' remittances incur costs if the emigrating workers are highly skilled, or if their departure creates labor shortages…. if remittances are large.. the recipient country could face an appreciation of the real exchange rate that may make its economy less competitive internationally…remittances can also create dependency, undercutting recipients' incentives to work, and thus slowing economic growth. But …the negative relationship between remittances and growth observed in some empirical studies may simply reflect the counter-cyclical nature of remittances—that is, the influence of growth on remittances rather than vice-versa.

Remittances may …have human costs. Migrants sometimes make significant sacrifices—often including separation from family—and incur risks to find work in another country. …they may have to work extremely hard to save enough to send remittances.

Can high transaction costs be cut?

Transaction costs are not …an issue for large remittances (made for the purpose of trade, investment, or aid), because, as a percentage of the principal amount, they tend to be small, and major international banks are eager to offer competitive services for large-value remittances. But in the case of smaller remittances—under $200, say, which is often typical for poor migrants—remittance fees can be as high as 10–15 percent of the principal (see table).

| Transfer costs Approximate cost of remitting $200 (percent of principal)

— Data not available. |

Cutting transaction costs would significantly help recipient families.

How…?

- the remittance fee should be a low fixed amount, not a percent of the principal, since the cost of remittance services does not really depend on the amount of principal. Indeed, the real cost of a remittance transaction—including labor, technology, networks, and rent—is estimated to be significantly below the current level of fees.

- greater competition will bring prices down. Entry of new market players can be facilitated by harmonizing and lowering bond and capital requirements, and avoiding overregulation (such as requiring full banking licenses for money transfer operators). The intense scrutiny of money service businesses for money laundering or terrorist financing since the 9/11 attacks has made it difficult for them to operate accounts with their correspondent banks, forcing many in the United States to close. While regulations are necessary for curbing money laundering and terrorist financing, they should not make it difficult for legitimate money service businesses to operate accounts with correspondent banks. An example where competition has spurred reductions in fees is on the U.S.–Mexico corridor, where remittance fees have fallen by 56 percent from over $26 (to send $300) in 1999 to about $11.50 now. In addition, some commercial banks have recently started providing remittance services for free, hoping that would attract customers for their deposit and loan products. And in some countries, new remittance tools—based on cell phones, smart cards, or the Internet—have emerged.

- establishing partnerships between remittance service providers and existing postal and other retail networks would help expand remittance services without requiring large fixed investments to develop payment networks. However, partnerships should be nonexclusive. Exclusive partnerships between post office networks and money transfer operators have often resulted in higher remittance fees.

- poor migrants need greater access to banking. Banks tend to provide cheaper remittance services than money transfer operators. Both sending and receiving countries can increase banking access for migrants by allowing origin country banks to operate overseas; by providing identification cards (such as the Mexican matricula consular), which are accepted by banks to open accounts; and by facilitating participation of microfinance institutions and credit unions in the remittance market.

Can governments boost flows?

Governments …often offered incentives to increase remittance flows and to channel them to productive uses. But such policies are more problematic than efforts to expand access to financial services or reduce transaction costs. Tax incentives may attract remittances, but they may also encourage tax evasion. Matching-fund programs to attract remittances from migrant associations may divert funds from other local funding priorities, while efforts to channel remittances to investment have met with little success. Fundamentally, remittances are private funds that should be treated like other sources of household income. Efforts to increase savings and improve the allocation of expenditures should be accomplished through improvements in the overall investment climate, rather than targeting remittances. Similarly, because remittances are private funds, they should not be viewed as a substitute for official development aid.

Friday, November 25, 2005

change of guard in Bihar

The change of guard in Bihar interests many, particularly to those rural poor which constitutes almost 50% of the total 83 million population of one of the poorest state of indian democracy. A study done by the World Bank on Bihar in 2003 showed 75 per cent of the rural poor were landless or near landless in 1999-2000. In rural areas, land ownership is closely linked to poverty, not just because land provides main source of income, but because land provides access to economic and social opportunities. Land reform in Bihar started in 1950s with the abolition of intermediaries between landlord and cultivators who worked under feudal lords. While the first Land Ceiling Act was passed in 1961, the progress has been very slow since. Only 1.5 per cent of the cultivable land was aquired and distributed by the ’80s,

In fact the Economist (26th Nov. 2005) in its current issue also highlighted the change of mis(rule) in Bihar.

...... Laloo Prasad Yadav had ruled Bihar since 1990…. it set the standard for bad government. Kidnapping for ransom was the only growth industry. Poverty, illiteracy, corruption and violence thrived. Mr Yadav's belated comeuppance came in an election result announced on November 22nd that left the RJD with just 54 out of 243 seats in Bihar's legislative assembly…..nothing to disguise their glee. “Laloo loses; Bihar wins�….. Even the RJD's ally, the Congress party, may not be too upset by the defeat of the biggest of its coalition partners in the central government.

Mr Yadav, who stood down as Bihar's chief minister in 1997 in favour of his wife after being charged with corruption, is India's railway minister….rise has been built on his skill at the politics of caste (read Yadav) and religion (read muslims)….earthily flaunted his humble origins as proof of his ability to bring dignity to the lower castes; and, allied with powerful gangsters, he presented himself as a protector of the Muslim minority.

….this year did this formula fail him, for a number of reasons. One was the job done by India's independent election commission, which kept the campaign relatively free of violence, and prevented “booth-capturing�—the coercion of voters…..Moreover, others, such as Bihar's new chief minister, Nitish Kumar, of the Janata Dal (United), have learned the art of caste-coalition building. Mr Yadav was deserted by many former supporters. His disdain for development, which has seen Bihar fall further behind on most social indicators, was, eventually, his undoing. Nor do Muslims now feel so worried by the rise of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), the main national opposition and Mr Kumar's partner, with its Hindu-nationalist ideology.

Monday, November 21, 2005

corporate social responsibility: fairy tale???

The Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Movement has grown…. from a fringe activity by a few earnest companies, like The Body Shop, and Ben & Jerry’s, to a highly visible priority for traditional corporate leaders from Nike to McDonald’s. Reports of good corporate behavior are now commonplace in the media, from GlaxoSmithKline’s donation of antiretroviral medications to Africa, to Hewlett-Packard’s corporate volunteering programs, to Starbucks’ high-volume purchases of Fair Trade coffee. In fact, CSR has gained such prominence that the Economist (22 Jan, 2005) devoted a special issue…. Although some see CSR as simply philanthropy by a different name, it can be defined broadly as the efforts corporations make above and beyond regulation to balance the needs of stakeholders with the need to make a profit. Though traces of modern-day CSR can be found in the social auditing movement of the 1970s, it has only recently acquired enough momentum to merit an Economist riposte.

….key events, such as the sinking of Shell’s Brent Spar oil rig in the North Sea in 1996, and accusations of Nike and others’ use of “sweatshop labor,� triggered the first major response by big business to the uprisings against the corporate institution. Naomi Klein’s famous tome, “No Logo,�(1) gave voice to a generation that felt that big business had taken over the world, to the detriment of people and the environment, even as that generation was successfully mobilizing attacks on corporate power following the Seattle anti-globalization riots in 1999.

…..corporations emerged brandishing CSR as the friendly face of capitalism, helped, in part, by the very movement that highlighted the problem of corporate power in the first place. NGOs, seeing little political will by governments to regulate corporate behavior, as free-market economics has become the dominant political mantra, realized that perhaps more momentum could be achieved by partnering with the enemy. By using market mechanisms via consumer power, they saw an opportunity to bring about more immediate change….organizations that address social standards in supply chains, such as the Fair Label Association in the United States or the United Kingdom’s ethical Trading Initiative, have flourished. The United Nations partnered with business to launch its own Global Compact, which offered nine principles relating to human rights and the environment, and was hailed as the ethical road map for the future.…..eventually the mainstream investment community cottoned onto CSR: In 1999, Dow Jones created the Dow Jones Sustainability Indexes, closely followed by the FTSE4Good. All of these initiatives have been premised on the notion that companies can ‘do well’ and ‘do good’ at the same time – both saving the world and making a decent profit, too. The unprecedented growth of CSR… lead some to feel a sense of optimism about the power of market mechanisms to deliver social and environmental change. But markets often fail, especially when it comes to delivering public goods; therefore, we have to be concerned that CSR activities are subject to the same limitations of markets that prompted the movement in the first place.

Making Markets Work?

At face value, the market has… been a powerful force in bringing forward some measurable changes in corporate behavior. Most large companies now issue a voluntary social and environmental report alongside their regular annual financial report; meanwhile the amount of money being poured into socially responsible investing (SRI) funds has been growing at an exponential rate, year over year….socially linked brands, such as Fair Trade, are growing very quickly. Ethical consumerism in the United Kingdom was worth almost £25 billion in 2004, according to a report from the Co-operative Bank.(2) The Economist article argued that the only socially responsible thing a company should do is to make money – and that adopting CSR programs was misguided, at best. But there are some strong business incentives that have either pushed or pulled companies onto the CSR bandwagon….. companies confronted with boycott threats, as Nike was in the 1990s, or with the threat of high-profile lawsuits, as McDonald’s is over obesity concerns, may see CSR as a strategy for presenting a friendlier face to the public….. CSR initiatives may provoke changes in basic practices inside some companies. Nike is now considered by many to be the global leader when it comes to improving labor standards in developing-country factories. The company now leads the way in transparency, too. When faced with a lawsuit over accusations of sweatshop labor, Nike chose to face its critics head-on and this year published on its Web site a full list of its factories with their audited social reports….. plethora of other brands have developed their own unique strategies to confront the activists, with varying degrees of success. But no one could reasonably argue that these types of changes add up to a wholesale change in capitalism as we know it, nor that they are likely to do so anytime soon.

Market Failure

One problem here is that CSR as a concept simplifies some rather complex arguments and fails to acknowledge that ultimately, trade-offs must be made between the financial health of the company and ethical outcomes. And when they are made, profit undoubtedly wins over principles. CSR strategies may work under certain conditions, but they are highly vulnerable to market failures, including such things as imperfect information, externalities, and free riders. Most importantly, there is often a wide chasm between what’s good for a company and what’s good for society as a whole. The reasons for this can be captured under what I’ll argue are the four key myths of CSR.

Myth #1: The market can deliver both short-term financial returns and long-term social benefits.

One assumption behind CSR is that business outcomes and social objectives can become more or less aligned. The rarely expressed reasoning behind this assumption goes back to the basic assumptions of free-market capitalism: People are rational actors who are motivated to maximize their self-interest. Since wealth, stable societies, and healthy environments are all in individuals’ self-interest, individuals will ultimately invest, consume, and build companies in both profitable and socially responsible ways. In other words, the market will ultimately balance itself. Yet, there is little if any empirical evidence that the market behaves in this way. In fact, it would be difficult to prove that incentives like protecting natural assets, ensuring an educated labor force for the future, or making voluntary contributions to local community groups actually help companies improve their bottom line. While there are pockets of success stories where business drivers can be aligned with social objectives, such as Cisco’s Networking Academies, which are dedicated to developing a labor pool for the future, they only provide a patchwork approach to improving the public good. In any case, such investments are particularly unlikely to pay off in the two- to four-year time horizon that public companies, through demands of the stock market, often seem to require.

As we all know, whenever a company issues a “profits warning,� the markets downgrade its share price. Consequently, investments in things like the environment or social causes become a luxury and are often placed on the sacrificial chopping block when the going gets rough. Meanwhile, we have seen an abject failure of companies to invest in things that may have a longer-term benefit, like health and safety systems. BP was fined a record $1.42 million for health and safety offenses in Alaska in 2004, for example, even as Lord John Browne, chief executive of BP, was establishing himself as a leading advocate for CSR, and the company was winning various awards for its programs. At the same time, class-action lawsuits may be brought against Wal-Mart over accusations of poor labor practices, yet the world’s largest and most successful company is rewarded by investors for driving down its costs and therefore its prices. The market, quite frankly, adores Wal-Mart. Meanwhile, a competitor outlet, Costco, which offers health insurance and other benefits to its employees, is being pressured by its shareholders to cut those benefits to be more competitive with Wal-Mart.(3) CSR can hardly be expected to deliver when the short-term demands of the stock market provide disincentives for doing so. When shareholder interests dominate the corporate machine, outcomes may become even less aligned to the public good. As Marjorie Kelly writes in her book, “The Divine Right of Capital�: “It is inaccurate to speak of stockholders as investors, for more truthfully they are extractors.�(4)

Myth #2: The ethical consumer will drive change.

Though there is a small market that is proactively rewarding ethical business, for most consumers ethics are a relative thing. In fact, most surveys show that consumers are more concerned about things like price, taste, or sell-by date than ethics.(5) Wal-Mart’s success certainly is a case in point.

In the United Kingdom, ethical consumerism data show that although most consumers are concerned about environmental or social issues, with 83 percent of consumers intending to act ethically on a regular basis, only 18 percent of people act ethically occasionally, while fewer than 5 percent of consumers show consistent ethical and green purchasing behaviors.(6) In the United States, since 1990, Roper ASW has tracked consumer environmental attitudes and propensity to buy environmentally oriented products, and it categorizes consumers into five “shades of green�: True-Blue Greens, Greenback Greens, Sprouts, Grousers, and Basic Browns. True-Blue Greens are the “greenest� consumers, those “most likely to walk their environmental talk,� and represent about 9 percent of the population. The least environmentally involved are the “Basic Browns,� who believe “individual actions (such as buying green products or recycling) can’t make a difference� and represent about 33 percent of the population.(7) Joel Makower, co-author of “The Green Consumer Guide,� has traced data on ethical consumerism since the early 1990s, and says that, in spite of the overhyped claims, there has been little variation in the behavior of ethical consumers over the years, as evidenced by the Roper ASW data. “The truth is, the gap between green consciousness and green consumerism is huge,� he states.(8) Take, for example, the growth of gas-guzzling sport-utility vehicles. Even with the steep rise in fuel prices, consumers are still having a love affair with them, as sales rose by almost 8 percent in 2004. These data show that threats of climate change, which may affect future generations more than our own, are hardly an incentive for consumers to alter their behavior.(9)

Myth #3: There will be a competitive “race to the top� over ethics amongst businesses.

A further myth of CSR is that competitive pressure amongst companies will actually lead to more companies competing over ethics, as highlighted by an increasing number of awards schemes for good companies, like the Business Ethics Awards, or Fortune’s annual “Best Companies to Work For� competitions. Companies are naturally keen to be aligned with CSR schemes because they offer good PR. But in some cases businesses may be able to capitalize on well-intentioned efforts, say by signing the U.N. Global Compact, without necessarily having to actually change their behavior. The U.S.-based Corporate Watch has found several cases of “green washing� by companies, and has noted how various corporations use the United Nations to their public relations advantage, such as posing their CEOs for photographs with Secretary-General Kofi Annan.(10) Meanwhile, companies fight to get a coveted place on the SRI indices such as the Dow Jones Sustainability Indexes. But all such schemes to reward good corporate behavior leave us carrying a new risk that by promoting the “race to the top� idea, we tend to reward the “best of the baddies.� British American Tobacco, for example, won a UNEP/Sustainability reporting award for its annual social report in 2004.(11) Nonetheless, a skeptic might question why a tobacco company, given the massive damage its products inflict, should be rewarded for its otherwise socially responsible behavior.

While companies are vying to be seen as socially responsible to the outside world, they also become more effective at hiding socially irresponsible behavior, such as lobbying activities or tax avoidance measures. Corporate income taxes in the United States fell from 4.1 percent of GDP in 1960 to just 1.5 percent of GDP in 2001.(12) In effect, this limits governments’ ability to provide public services like education. Of course, in the end, this is just the type of PR opportunity a business can capitalize on. Adopting or contributing to schools is now a common CSR initiative by leading companies, such as Cisco Systems or European supermarket chain Tesco.

Myth #4: In the global economy, countries will compete to have the best ethical practices.

CSR has risen in popularity with the increase in reliance on developing economies. It is generally assumed that market liberalization of these economies will lead to better protection of human and environmental rights, through greater integration of oppressive regimes in the global economy, and with the watchful eye of multinational corporations that are actively implementing CSR programs and policies. Nonetheless, companies often fail to uphold voluntary standards of behavior in developing countries, arguing instead that they operate within the law of the countries in which they are working. In fact, competitive pressure for foreign investment among developing countries has actually led to governments limiting their insistence on stringent compliance with human rights or environmental standards, in order to attract investment. In Sri Lanka, for example, as competitive pressure from neighboring China has increased in textile manufacturing, garment manufacturers have been found to lobby their government to increase working hours.

In the end, most companies have limited power over the wider forces in developing countries that keep overall wage rates low. Nevertheless, for many people a job in a multinational factory may still be more desirable than being a doctor or a teacher, because the wages are higher and a worker’s rights seem to be better protected.

What Are the Alternatives to CSR?

CSR advocates spend a considerable amount of effort developing new standards, partnership initiatives, and awards programs in an attempt to align social responsibility with a business case, yet may be failing to alter the overall landscape. Often the unintended consequences of good behavior lead to other secondary negative impacts, too. McDonald’s sale of apples, meant to tackle obesity challenges, has actually led to a loss of biodiversity in apple production, as the corporation insists on uniformity and longevity in the type of apple they may buy – hardly a positive outcome for sustainability.(13)

At some point, we should be asking ourselves whether or not we’ve in fact been spending our efforts promoting a strategy that is more likely to lead to business as usual, rather than tackling the fundamental problems. Other strategies – from direct regulation of corporate behavior, to a more radical overhaul of the corporate institution, may be more likely to deliver the outcomes we seek. Traditional regulatory models would impose mandatory rules on a company to ensure that it behaves in a socially responsible manner. The advantage of regulation is that it brings with it predictability, and, in many cases, innovation. Though fought stridently by business, social improvements may be more readily achieved through direct regulation than via the market alone. Other regulatory-imposed strategies have done more to alter consumer behavior than CSR efforts. Social labeling, for example, has been an extremely effective tool for changing consumer behavior in Europe. All appliances must be labeled with an energy efficiency rating, and the appliances rated as the most energy efficient now capture over 50 percent of the market. And the standards for the ratings are also continuously improving, through a combination of both research and legislation.

Perhaps more profoundly, campaigners and legal scholars in Europe and the United States have started to look at the legal structure of the corporation. Currently, in Western legal systems, companies have a primary duty of care to their shareholders, and, although social actions on the part of companies are not necessarily prohibited, profit-maximizing behavior is the norm. So, companies effectively choose financial benefit over social ones.(15) While a handful of social enterprises, like Fair Trade companies, have forged a different path, they are far from dominating the market. Yet lessons from their successes are being adopted to put forward a new institutional model for larger shareholder-owned companies. In the United Kingdom, a coalition of 130 NGOs under the aegis of the Corporate Responsibility Coalition (CORE), has presented legislation through the Parliament that argues in favor of an approach to U.K. company law that would see company directors having multiple duties of care – both to their shareholders and to other stakeholders, including communities, employees, and the environment. Under their proposals, companies would be required to consider, act, mitigate, and report on any negative impacts on other stakeholders.(16)

Across the pond, Corporation 20/20, an initiative of Business Ethics and the Tellus Institute, has proposed a new set of principles that enshrines social responsibility from the founding of a company, rather than as a nice-to-have disposable add-on. The principles have been the work of a diverse group including legal scholars, activists, business, labor, and journalism, and while still at the discussion phase, such principles could ultimately be enacted into law, stimulating the types of companies that might be better able to respond to things like poverty or climate change or biodiversity. Values such as equity and democracy, mainstays of the social enterprise sector, take precedence over pure profit making, and while the company would continue to be a profit-making entity in the private realm, it would not be able to do so at a cost to society.

Of course, we are a long way from having any of these ideas adopted on a large scale, certainly not when the CSR movement is winning the public relations game with both governments and the public, lulling us into a false sense of security. There is room for markets to bring about some change through CSR, but the market alone is unlikely to bring with it the progressive outcomes its proponents would hope for. While the Economist argument was half correct – that CSR can be little more than a public relations device – it fails to recognize that it is the institution of the corporation itself that may be at the heart of the problem. CSR, in the end, is a placebo, leaving us with immense and mounting challenges in globalization for the foreseeable future.

Notes:

- N. Klein, No Logo: Taking Aim at the branding Bullies (UK: Harper-Collins, 2001)

- Co-operative Bank, 2004

- A. Zimmerman, “Costco’s Dilemma: Be Kind to Its Workers, or Wall Street?� Wall Street Journal, march 26, 2004

- M. Kelly, The Divine Right of Capital:Dethroning the Corporate Aristocracy (San Francisco: Berrett Koehler, 2003)

- “Who are the Ethical Consumers?� Co-operative 2000

- Green Gauge Report 2002, Roper ASW, as related by Edwin Stafford

- http://makower.typepad.com/joel_makower/2005/06/ideal_bite_keep.html

- http://money.cnn.com/2004/05/17/pf/autos/suvs_gas/

- “Greenwash + 10: The UN’s Global Compact, Corporate Accountability, and the Johannesburg Earth Summit,� Corporate Watch, January 2002

- “The Global Reporters 2004 Survey of Corporate Sustainability Reporting.� SustainAbility, UNEP, and Standard & Poor’s

- J. Miller, “Double Taxation Double Speak: Why Repealing Tax Dividends is Unfair,� Dollars and Sense, March/April2003

- G. Younge, “McDonald’s Grabs a Piece of the Apple Pie: ‘Healthy’ Menu Changes Threaten the Health of Biodiversity in Apples,� The Guardian, April 7, 2005

- Ethical Purchasing Index, 2004

- E. Elhauge, “Sacrificing Corporate Profits in the Public Interest,� New York University Law Review 80, 2005

- www.corporate-responsibility.org